Lewes & Diversity – We All Had Our Say

November 26, 2010

On Tuesday, November 23rd I was one of three speakers at Lewes & Diversity: Have Your Say, a standing room only event at Pelham House in Lewes. Simon Woolley of Operation Black Vote and Dr Yaa Asare a Brighton academic were the other two speakers. I was also pleased to have been one of the team who had organised the event, though others worked far harder than me to make it happen.

Here is the text of my talk:

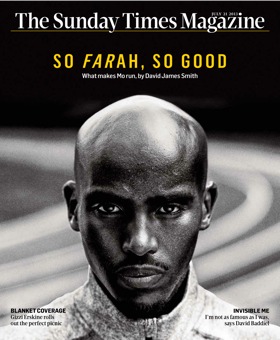

As I guess most of you know I wrote an article for the Sunday Times Magazine about my family’s experience of minor incidents of racism, in the five years since we moved to Lewes from Fulham in south west London.

I thought it might be interesting and helpful tonight if I supplied some context to the article and helped you to understand what I was trying to say and why I was saying it, and what i was hoping to achieve. I say, I, but in fact, although the article was written by me and appeared under my byline it was first and foremost based on the thoughts and experiences of my partner Petal. Like our famous Lewesian poets, Grace Nichols and John Agard, Petal’s family come from Guyana, a country on the rump of mainland South America which culturally looks more to the islands of the Caribbean. All the black people in Guyana, as in the Caribbean are the descendants of plantation slaves.

That is a part of Petal’s heritage and a part of the heritage of our four mixed race children. Petal and I have been together for more than 30 years and our eldest child is 16. We had more or less always lived as a couple in Fulham, and while racism was inevitably a presence in our lives – well, in Petal’s – especially when she worked at the BBC – it was not especially oppressive. I did not go around worrying about it, much less writing about it. I tried to understand it, and its effect, but far beyond that I revelled in the richness of Caribbean culture, the warmth and kindness of the people, its music, its food, the vibrancy and diversity of its approach to the English language and its literature, much of which I think, still remains unknown to many.

That was the atmosphere in which we tried to raise our children. You can choose to raise children of dual heritage any way you want, but it seemed obvious to us that they were essentially mixed race black, and it was that blackness we wanted them to embrace and celebrate. We sent them to a nursery run predominantly by black staff, predominantly for black children. That wasn’t a big political statement, it just seemed like the natural thing to do.

I was not, as some have suggested, a ‘racist hunter’ going aroound sniffing out suspicious behaviour by others. Nor indeed writing about racism at every opportunity. I have only ever been a journalist, I have written for the Sunday Times Magazine since the 1990s and though articles have touched on race from time to time, this article was the most personal I had ever written and the only time I have ever written directly about racism.

People have suggested I wrote the article – cycnically – to promote a book I had written about Nelson Mandela. Well, of course, every writer wants to be read as much as possible, otherwise why bother writing. But I am just not that cycnical person of other people’s imagining, just as I am not generally the person many people have assumed me to be since the article appeared.

Perhaps, in broad terms, I was thinking more about race than usual because I was thinking about Mandela’s fight against apartheid. But that was not the reason i wrote the article.

It emerged essentially out of a conversation with a new editor at the Sunday Times Magazine.

Sarah Baxter had just finished being the Washington correspondent of the paper and had reported Barack Obama’s thrilling ascent to the Presidency. We have quickly forgotten how much that meant to so many, to black people around the world who claimed Obama with pride. Petal’s niece and her husband flew to Washington just to be around his inauguration. They sent us the front page of the Washington Post. It was a transforming moment and started a slightly silly global discussion about how a black man becoming President meant no more racism. It meant we had entered a post-racial world.

How great that would be, but sadly it is not the case. Oh yes, I said to my editor a bit sarcastically, we are all living in a post racial world now. I was thinking mainly of Petal who had started to feel quite isolated in Lewes. Not because she didnt have friends or had not involved herself in the life of the town. She had, and did have many friends; we both did. We had and – miraculously you may think – still have great friends, some of whom we love dearly. But there was something that was often missing and that was an awareness and understanding of diversity that we had kind of taken for granted in London.

Of course, Lewes is full of ex Londoners, but it is just naturally far less racially diverse and that means people do not always understand the nuances of race and racial awareness.

One or two people had told Petal there was no racism in Lewes. That troubled Petal, not because those people were being racist themselves but because it betrayed a lack of awareness. It was well meant, undoubtedly, but seemed to suggest those people thought Lewes was some kind of utopian idyll, which of course it is not. Perhaps if those people had paused to consider the effect of what they were saying they might have put it differently. Two people said it on two different occasions. There were so many small incidents, too many even for that long article I wrote. Petal has a fantastic memory and remembered them all. She started to feel – she told me – like she was being silenced. Very visible in one way – everyone knew her or thought they did because she stood out by virture of her blackness, but invisible because she was feeling things that others could not grasp.

That was the difficult territory I tried to enter into in my article. I knew instinctively, of course, that this was not simply Petal’s view but had been – and would be – repeated across the white towns and villages of non urban England. Black people generally did not go to those places, they clustered together in the cities. But they had as much right to live in Lewes as Lewisham and to expect to be treated the same as everyone else.

We were especially concerned about our children being isolated in school. People have complained – perhaps with some justification – that I exposed the children to problems by having them appear in photographs in the article. It was a decision Petal and I agonised over. I believed they were already highly visible anyway and that it was something we ought to be proud to stand up for together as a family.

Yes the article would be provocative, yes it would attract criticism, those critics in the main were people you were never going to win over or change. But perhaps there were many people – more open minded – who might want to pause and consider what the article was trying to convey: the main idea for me was that racism is not what it used to be, not about open hostility but about small, subtle incidents that many would not think racist at all but could be highly damaging to those affected, especially if they were children.

There was – and still is – a common use of racist language in the playground at Priory. The school has a new head who has shown a ready grasp of these concerns and a willingness to address race issues. People I know who teach in other schools locally tell me they are often surprised by the very conservative and unworldly views on cultural diversity held by their students. Our daughters have been touched by these kinds of difficulties and we were doubly concerned that our son, still at primary school could be affected by them. Statistically, as an African-Caribbean boy, even one of mixed race, he was likely to do less well than his white peers at secondary. At least one factor would be the expectations of culturally unaware teachers.

Priory had never previously celebrated black history. Of course, it might say it hadn’t needed to, as there were next to no black students. But celebrating black achievement might help to improve awareness and would make the white students more rounded individuals when they stepped out into the world. The same might be true not just for race but for their attitude to gay men and women, to same sex relationships, to disability and all the other supposed differences that are nowadays merely part of the fabric of our lives.

My article was not originally just about us. In its initial draft it embraced interviews I had conducted with many other black and Asian people living in Lewes. Their stories were often more hair raising than ours, they had experienced more overt racism. There was the mixed couple whose daughter had been excluded by school friends forming a ‘white club’ to which they told her she could not belong; there was the black African man who found he had to put up constantly with little racist jokes about his ‘tan’ or being invisible at night. He did not like challenging people. No doubt if he challneged people they would have thought him touchy or over sensitive. Perhaps they would have accused him of having a chip on his shoulder. An Asian man had been openly racially abused on two occasions in the town…I could go on and on. I tell you these stories not because i think Lewes is a hotbed of racism, but because i hope people will be more aware, will perhaps pause before they dismiss the claims, and perhaps accept that predominantly white communities are not

always as clued up about race and racism as they think they are.

I am sorry and surprised that people have taken my article to condemn Lewes as that hotbed of racism. That phrase does not appear anywhere in the article, nor any phrase like it. Nor is that idea inferred or implied anywhere in the text.

Some black people – including some of those I interviewed – have said they wished more of those stories of more obvious racism had been included as it would have made the article stronger and less easy to dismiss or deny. Maybe they are right, I only know that the article was too long, it had to be cut, and we decided it would read better if it was just about us, which suited my aim of addressing that subtle area of racism which i think is more difficult to understand.

An example might be a remark another boy made about our son having big nostrils. I included that in the article and people have thought I was saying the other boy was racist, but that was not my intention at all. My point about that remark – Petal’s point really, it was she who recalled this incident for me, she could speak herself she is here and not exactly a shrinking violet as those of you who know her will testify – her point about the nostrils’ remark was that it added to her growing concerns that Mackenzie was being singled out and made to feel different because of his race. In London, or Lusaka, or Limpopo, his nostrils would have been unremarkable, but here in Lewes we worried he would start to feel different, not normal.

People will say – people have said – ahh, its just his nostrils, everyone gets mocked for having big ears, spots, glasses, anything that makes them standout. But our son could have any of those things too. What anyone can’t have is his gorgoeus African nose – something in our view to be admired and cherished not make him feel uncomfortable about. Perhaps that will change as Lewes becomes more diverse and more black people come to live in the town.

That was just one of a series of little incidents that caused Petal and I concern about our son and how he would be viewed. I wanted to write about it because it was important to us and I hoped people might stop and think – oh, okay, i can see that must be a bit worrying.

I guess some people have paused and have had those thoughts.

Thank you.