The critics on Young Mandela

New York Times – J. M. Ledgard

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. They exclaimed, “Ndiyindoda!” (“I am the man!”). A brambly leaf was wrapped around the wound to stop the bleeding. The boys had to lie in a certain position, and at midnight they were woken. One by one, they went out into the cold and buried their foreskins in stony soil. For Mandela, the circumcision was something that linked him with his Thembu ancestors; in losing a part of his manhood, he became a man.

The surprise in these three very different books is how darkly and deeply the former South African president’s life reads like an African quest narrative. For those who know Mandela’s background, it may seem impertinent to suggest that his story reads like an African one — the fact is that almost all of Africa’s liberation leaders came out of a few elite schools, and their coming-of-age was a lurch from hymnals to Marxism, never quite forgetting the Battle of Agincourt. Consider that Fort Hare, the black college Mandela attended in South Africa, counted Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, Tanzania’s Julius Nyere, Botswana’s Seretse Khama and Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda as alumni, with Desmond Tutu serving briefly as its chaplain, and you get a sense of how small the pool was. None of the leadership academies now fashionable in Africa will ever approach the influence of places like Fort Hare.

It was natural, in such an environment, to be conflicted about the countryside, the “deep time.” Set against the latest Penguin paperback or a faraway atomic achievement, the village looked dim and isolated; yet it was also embracing. “I hardly remember any occasion when I was ever alone at home,” Mandela recalls in “Conversations With Myself.” “There were always other children with whom I shared food and blankets at night.”

Mandela’s quest narrative begins with the dispossession of his father from a chieftaincy, perhaps for standing up to the British, and the struggle of the young Mandela to find his place in the Thembu royal court. He did so with characteristic grace, physicality and determination. He was chosen to attend a Methodist boarding school, then Fort Hare. He refused a traditional marriage and made his way to Johannesburg. There he was taken under the wing of Walter Sisulu, the father figure of the African National Congress, and set up a law firm with Oliver Tambo, a friend from Fort Hare who became head of the A.N.C. in exile when Mandela and other leaders were imprisoned in 1962.

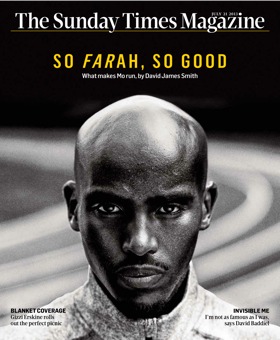

David James Smith’s “Young Mandela” takes up the tale of Mandela’s rise within the A.N.C. in gripping fashion. Smith, who writes for The Sunday Times Magazine of London, says a decisive moment occurred when Mandela was rejected on racial grounds from completing his law studies at Witwatersrand University. Mandela went on to become close to the white Communists and Asians in the A.N.C., but “believed the struggle was the struggle of black Africans, first and foremost.” He was abstemious, but also a dandy. He quoted Jawaharlal Nehru’s phrase “There is no easy walk to freedom,” and his politics were certainly to the left of Nehru’s Fabian socialism; still, he admired the pomp of Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia.

The second part of the quest was the overcoming of self. This happened in prison. Incarceration was another kind of deep time for him. Most of it was spent on Robben Island, off the coast of Cape Town. It was sunlit, windswept, with clean air, but also foul, concrete and entirely European in tone. Mandela was released in 1990, a few weeks after the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

The rhythms of prison life are dealt with in “Conversations With Myself.” Mandela’s prison entries are terse, often just a line on a wall calendar for a passing day. “24 March 1989 Visited by Mandla” — his grandson — “from 11.30 a.m. to 1.30 p.m. Brought Sakharov Award. Scroll and cheque and medal.” Then again, arbitrariness is what makes “Conversations With Myself” such dramatic reading. And there are plenty of interesting details. For instance, we learn that there was more contact between the A.N.C. and the apartheid regime than the public suspected. Mandela met with the head of the apartheid intelligence service, Niel Barnard, in the 1980s. Two other Robben Island prisoners were delegated by the A.N.C. to talk with Barnard: these were the future South African presidents Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma.

Mandela’s prison experiences are distilled into the life lessons of “Mandela’s Way,” a highly commercial book by Richard Stengel, the editor of Time magazine and the collaborator with Mandela on his autobiography. Prison, Stengel says, taught Mandela how to deal with limits and how to govern his emotions; at the same time it taught him what was limitless, which was, broadly, the potential of humanity to do the right thing. Be constructive, Mandela advises, be pragmatic, be generous; look for the good in others. Mandela cultivated the mix of bluntness and courtesy Afrikaners respected; he managed to disarm the apartheid president, P. W. Botha, a harsh man, “with a robust handshake and a wide smile.”

Even if you are beaten down, we are instructed, cultivate confidence. Pay attention to your appearance and your health; don’t whine, work out. Understand that image endures. “All his life, he cultivated and curated images of himself.” Therefore, your biggest asset is your smile. Feel free to change your mind; have no favorites; hold your counsel. Whatever your circumstances, do something life-affirming: for Mandela, it was his prison garden of 32 oil drums in which he grew vegetables and fruit.

The third part of Mandela’s quest was freedom. He became an icon and the founding president of the new South Africa. Though there were scores to settle, Mandela chose the path of truth and reconciliation. But in the fourth and final part of the quest, his figurative coming home, the narrative strays. This hero does not come home, cannot in fact come home. Although there is personal happiness in a marriage to Graça Machel, the widow of the Mozambican president Samora Machel, the cost of the odyssey is counted on those close to him. Mandela found his first wife, Evelyn, ill-fitting. She became a Jehovah’s Witness, considered him an adulterer who abandoned his children and accused him of beating her (a charge Mandela denied). His marriage to Winnie Mandela scarcely survived their prison sentences. One son was estranged from him and killed in a car accident in 1969; another was an alcoholic who died of AIDS in 2005. Smith suggests that Mandela had another son born out of an affair with an A.N.C. comrade.

So which book to buy? One suspects “Mandela’s Way” will never escape the bathroom, though it is to be commended for the way it distills unparalleled access to Mandela for a wider audience. “Conversations With Myself” is outstanding for what it offers (especially given Mandela’s less than Tolstoyan approach to writing). Its collection of letters and meditations, together with its thorough index and appendix, belongs on the shelf of anyone interested in the nature of power and resistance. Yet the only one of these books that meets its goal of offering a fresh portrait of this modern-day saint is “Young Mandela.” Here, you think, is the man.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011