The critics on Young Mandela

The Sunday Times – Stephen Robinson

Before he went underground in 1961 to mastermind the ANC’s guerrilla campaign, Nelson Mandela released a lengthy statement, of which only five words are now remembered: “The struggle is my life.”Ever since, he has been lauded for his selflessness, but as this biography unblinkingly reveals, his family had already learnt that politics squeezed everything else out, leaving them embittered in the shadow of his global celebrity.

Nobody will be surprised to learn that, in his youth, Mandela chased women who didn’t run very fast. He was an exceptionally charismatic young lawyer in Johannesburg, who had his suits cut at the best tailor in town just opposite the Rand Club, where rich white men gathered to discuss high finance and the native question.

The anti-apartheid movement of the 1950s and 1960s might have been built upon fighting injustice, but it was fuelled by alcohol and libido, and many of the white communists were just as keen as the black nationalists to use politics — as David James Smith relates — to get their hands into girls’ pants. Mandela’s behaviour was unusual only in his emotional neglect of his wives and children. He shunned even his own mother, whom he rarely saw before he went to prison, apparently because he was embarrassed by her lack of education. He drove his first wife, Evelyn, close to madness by his casual adultery, allowing one lover to walk into the marital bedroom while she was present in their cramped Soweto house. Evelyn threatened to throw boiling water over the woman if he brought her home again.

There were numerous other women apart from Evelyn and his second wife, Winnie; almost certainly an unacknowledged illegitimate child; and allegations by poor, bitter Evelyn in her divorce petition that he had beaten her. The mystery of Mandela lies in the jarring contrast between his behaviour towards his family, and his princely courtesy to everyone else.

When he was arrested in 1962 for his ANC activities, he came up before a grim pro-apartheid magistrate who would take lunch with special-branch officers. This offered the defence an opportunity to demand the magistrate recuse himself, but Mandela was oddly reluctant to humiliate the man, and insisted that good manners required he be given warning of the application. Again and again, reading this book, one wonders what prevented Mandela extending the same sort of kindness to his own family.

Admittedly, for much of his life he was not in a position to take control, yet some of his children clearly resented him before he was sent to Robben Island in 1964. His son Thembi, who died in a car crash five years later, had not once visited his father in jail. In 2004, when another son, Makgatho, succumbed to complications from Aids, Mandela was unable to hold his hand around his hospital bed as he died. Subsequently Mandela was lauded for announcing that Makgatho had died because of a virus that remains taboo in South Africa, yet Makgatho’s children regarded it as a betrayal of their father’s privacy.

Smith has certainly not taken a hatchet to Mandela in this book; rather, he succeeds in bringing him to life, wading in where other biographers have feared to tread to provide much new information and genuine insight. Young Mandela is not just an account of his early years, but also a superbly framed snapshot of the ANC’s transformation in the early 1960s into a guerrilla organisation, when rich white communists with swimming pools joined forces with angry black nationalists. The activists’ hapless attempts to strike terror into the heart of apartheid are sympathetically told, but their amateurism is starkly — and sometimes hilariously — portrayed. Few of them knew how to hold a gun or handle explosives. Mandela once attempted to prove his guerrilla credentials by shooting a sparrow out of a tree with an air gun, and then felt awful about it. When the security police belatedly realised that the sabotage campaign was based at Liliesleaf farm in the Johannesburg outer suburb of Rivonia, the guerrillas failed even to burn incriminating documents that became the basis of the prosecution case.

Mandela, Joe Slovo, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki et al were all fine men in their own ways, but it is difficult to disagree with Smith’s judgment that by prematurely launching an inept campaign of violence in 1961, “they incited a fierce clampdown by the state and set back their cause for a generation”.

Ultimately, Mandela and his comrades were fortunate that Pretoria buckled under intense secret diplomatic pressure and ensured that the conspirators were given life sentences rather than death, and of course we are all lucky for that, too.Smith has pitched this biography so well that by the end of it you are no less willing to join in the global celebration of Mandela’s stoicism and political acumen, even as you give thanks that you are not his wife or child.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

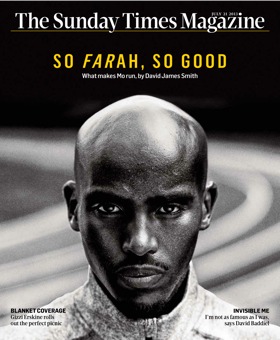

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011