The critics on Young Mandela

The Guardian – Mark Gevisser

There could not be a more poignant moment for the release of a book about Nelson Mandela’s personal life, and the complex interplay of political imperatives and family commitments that have bedevilled it. On the eve of the World Cup that he was to preside over as his final glorious public act, Mandela’s great-granddaughter was killed in a car accident; the driver, a member of the extended Mandela family (although not related by blood), has been accused of being drunk. Young Mandela is the backstory.

Mandela’s older son, Thembi, died in a car-crash while his father was in jail, in 1969; so alienated was the young man from his father that he had not visited him in prison on Robben Island. Mandela’s younger son, Makgatho, was an alcoholic who died of an Aids-related illness in 2005. According to David James Smith’s informants, he was a gentle sort deformed by his authoritarian father’s incapacity for affection and “unrelenting scrutiny”.

Mandela’s granddaughter Ndileka tells Smith Makgatho descended into alcoholism because of these deep wounds, and recounts a troubling story about how she failed to affect a death-bed reconciliation: Mandela “was frozen. He just could not accept his own feelings. Granddad can be affectionate with strangers but he is completely cut off from his own family.”

Thembi and Makgatho’s mother was Mandela’s first wife, Evelyn, who died in 2004. She left him, she claimed in the divorce papers, because of his womanising, neglect and violence; immediately the divorce came through, he married Winnie, and there has been tension between the “first family” and the “second family” ever since. The womanising allegations have been aired before; now, Smith names names: the singer Dolly Rathebe, the ANC women’s leader Lilian Ngoyi, his legal secretary Ruth Mompati, who allegedly bore his son.

The violence allegations are the most serious: Evelyn claimed Mandela beat and throttled her, and threatened to kill her with an axe. Smith spends some time trying to understand how Mandela could have done this: he was “very patriarchal”, and perhaps, given all the political pressure he was under, he simply “blew a gasket” in what was obviously a bad match. He comes to the conclusion that there must be “at least some credence” to the allegations, despite the fact that Mandela has categorically denied them, that they were not tested in court, and that they might have been fabricated or exaggerated by the aggrieved complainant. This is strong stuff, and is part of Smith’s stated intention, from the outset, “to rescue the sainted Madiba from the dry pages of history, to strip away the myth and create a fresh portrait of a rounded human being”.

At the very least, this is a long-overdue exploration of the making of the Mandela myth; one that refreshes a somewhat stale and overcrowded field. Smith sets the territory by looking at the stark difference between Mandela’s account of his father, a Thembu noble and a colonially appointed headman, and the documentary evidence provided by the colonial archive. He then effectively demonstrates how Mandela’s memoir was designed to “boost” the cult around him: although Mandela instructed his comrades to insert the line, “I led a thoroughly immoral life”, into Long Walk to Freedom, an “admission of immorality might have detracted, or at the very least distracted, from his heroic reputation”. And so “history had been revised”.

Of course, this last comment is the very definition of memoir, all the more so for someone who has exercised such tight control over his pubic image. Mandela has made a political fetish of his biography: as he was in chains, so too were all South Africans; as he liberated himself and forgave his oppressors, so too can we all expunge the hate from our hearts. For this reason, the most striking and valuable parts of Young Mandela are the rare occasions where we hear Mandela’s unmediated voice, in a series of exquisite letters to Winnie and his daughters from jail. Here, away from the public eye, he articulates acute emotional intelligence and deep regret as he recounts the way his calling has denied his children a normal family life.

The book also includes some well-researched recapitulations of key political moments in Mandela’s early life: the retelling of his time underground stands out, as does the description of the “double-life” of his white comrades. But I put the book down not so much with a clearer understanding of the making of Mandela as with the kind of headful of gossip you carry away after spending too much time in a small town.

Perhaps this is a comment on the small town of the Mandela industry itself: Cranford-on-the-Highveld. Like all gossip, some of it is illuminating, but much is gratuitous, unsubstantiated and even malicious: Smith is obsessed with the sexual goings-on of the white left, which tell us nothing about Mandela’s own infidelities; he uses unnamed sources to have a go at Maki, Mandela’s oldest daughter, for declining to be interviewed; he also twice reports on “suspicions” about the bona fides of Mandela’s co-accused Govan Mbeki, with no evidence to back it up. More seriously, he has no firm corroboration of the allegation that Mompati bore Mandela’s son, something she firmly denies.

Smith also does not give enough weight to the way revisionism and self-mythologisation is often a balm to the wounds made by history rather than an act of wilful intent. Often, too, he does not look closely enough at the reasons for the disjuncture between Mandela’s public memory and the conflicting evidence he has found; this is most evident in the case of the colonial record about Mandela’s father.

Ultimately, despite his strong research and laudable intentions, Smith falls into the mythbuster’s trap. Some people “won’t hear a word against” Mandela, he writes, and so sets himself the task of finding all the “words against” he can. In so doing, he sometimes loses sight of the primary reason for biography, which is to make sense of a life within its times, and to bring us closer to understanding its subject.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

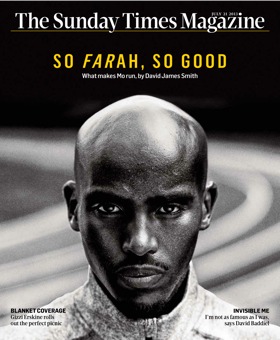

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011