The critics on Young Mandela

The Observer – Justin Cartwright

Last week it was announced that Nelson Mandela’s 13-year-old great-granddaughter, Zenani,named after one of Mandela’s two children by Winnie, was killed in a car crash on the way home from the World Cup opening party. The driver was allegedly drunk. Mandela said that he would not be attending the official ceremony. That a great-granddaughter of the most famous man on earth could have been entrusted to a drunk beggars belief. I raise this tragedy because it seems to me to be horribly familiar. Mandela’s families – there are two – have suffered appallingly as a result of his fame and his devotion to the anti-apartheid struggle. The succeeding generations have been racked by instability, and they continue a sometimes bitter competition for influence, money and – as some of them see it – ownership of the Mandela brand, competition that boiled over most recently when the ageing Mandela was enlisted to support Zuma’s election.

No one has been affected more than Winnie Mandela. Married young and soon separated from her much older husband, she was brutalised by the regime to such an extent that – in the charitable version of her life – she was so disturbed as to be complicit in terrible violence towards a young boy, Stompie Seipei. She was almost certainly guilty of ordering the killing by her “football club” of her own doctor and devoted supporter, Abu-Baker Asvat, when he was subpoenaed to give evidence after he examined Stompie shortly before his death. The doctor’s receptionist was Albertina Sisulu, whose husband, Walter, was Mandela’s first sponsor and closest ally. Although Sisulu described the events in detail at the time, she claimed in 1997 at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to have seen nothing. The only conclusion a reasonable person could come to is that she was leant upon to protect the Mandela name.

One of Mandela’s sons by his first marriage, Thembi, died in a car crash in 1969, and another, Makgatho, died of Aids in 2005. Thembi, although living in Cape Town, had never visited his father on Robben Island. Both sons were left rudderless by Mandela’s desertion of Evelyn, their mother. And Winnie has often said that her brief life with Mandela was appallingly insecure and that she hardly had a family life: he had famously proclaimed at his trial in 1961 that the struggle was his life.

David James Smith finds evidence that Mandela was in many ways a traditional African, who regarded himself as head of the family and expected to be obeyed. This is hardly a surprise. He also produces evidence that Mandela may sometimes have hit his first wife, Evelyn, and that he had a child by another woman. Evelyn retired eventually to the Transkei and lived on in embittered silence, although she talked to an earlier Mandela biographer, Fatima Meer, saying that Nelson was the only man she had ever loved and that he was a wonderful father.

It has never been a secret in Johannesburg that there was a different side to Mandela, that of a compulsive womaniser with a taste for fame, a dandy, a boxer, a man with an iron will. I was told some years ago by Breyten Breytenbach, the Afrikaner poet, who was imprisoned for seven years after a tip-off from the African National Congress (ANC), which distrusted his secret mission to South Africa, that the ANC leadership were utterly ruthless; they had been exposed to hardships and humiliation in their own country that made them, as he put it, quite different. As this book makes clear, the white, mainly Jewish, communists who were in alliance with the ANC lived their lives in the affluent suburbs with swimming pools and servants. Even when Mandela was living in hiding at Liliesleaf Farm, to the north of Johannesburg, the nominal owner of the farm, a communist called Arthur Goldreich, was taking riding lessons, while Mandela lived in a bare servant’s room to maintain his cover as a “garden-boy”.

Despite having innumerable reasons to hate white people, Mandela never allowed himself or the ANC to take the strictly Africanist route followed by the PAC (Pan Africanist Congress of Azania), and now increasingly by the ANC youth league. He believed that there could be no compromise with the principle of non-racialism. Towards the end of the 50s he was recognised by his comrades as the man to symbolise the ANC. It was he who brought the ANC round to the idea of the armed struggle and he was the first leader of the military wing, MK, the spear of the nation. It was understood that Mandela would sooner or later be captured and possibly hanged. That was his role, and he accepted it, while understanding the consequences. Yet Mandela’s letters from prison demonstrate that he never stopped feeling guilty about leaving Winnie and his daughters at the mercy of the regime, though he seems to have had less intense feelings for his first family. One of his granddaughters has said that no one who went into the struggle should have had a family.

The greatness of Mandela is not diminished by his adulteries and his desertions or his inability to demonstrate affection for his children. It lies in his unshakable resolve to produce a fair and humane society for all in South Africa, a legacy now under threat. It seems to be true, however, that he found it far easier to feel deeply for the oppressed than for his own family. Smith tells a moving story of his daughter Maki’s placing his hand on his dying son Makgatho’s hand as a gesture of reconciliation with his first family, but Mandela withdrew immediately. “He was frozen,” said a granddaughter who was present.

This book is valuable and fascinating, in the new detail it brings to the account of Mandela’s life, from his first acquaintance with the ANC to his imprisonment in June 1964, an imprisonment that caught the imagination of the world but destroyed his family.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

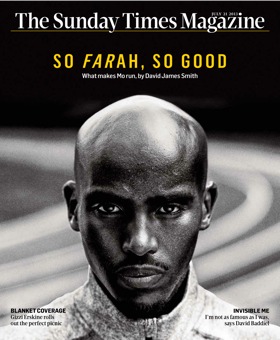

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011