The critics on Young Mandela

The Daily Telegraph – Gillian Slovo

On the back cover of Young Mandela, David James Smith has nailed the purpose behind his new addition to the burgeoning Mandela library: he wanted to explore not the icon but the human being. “He knows he is not a saint,” was the apparent plea from Madiba’s nearest and dearest. “He has flaws and weaknesses just like everyone else.” Thus is the ground laid for this warts-and-all account of Nelson Mandela’s life, loves and politics up until the day he was sent to Robben Island.

The book starts by describing Mandela’s origins and influences that led to the moment when, aged 23, he ran away from an arranged marriage. The snapshot of the old South Africa, with the fading tribal structure collaborating with the white state against the youth who would rise up to challenge both, is convincingly, if sketchily, evoked.

If there is a slight air of pedantry about the early sections (the author is at pains to work out the dates at which his second wife Winnie ate with Mandela in what once had been his home with his first, Evelyn) then this is because the book covers ground well dug by earlier biographies and so the author should explain when he diverges from previously declared “facts”.

He writes about the first Mandela family (Evelyn’s) and the second (Winnie’s) readably enough, restoring to both women some of the humanity that the glare of the spotlight had removed. And he takes care to lay the ground for the significant meetings and joining with Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, the two great comrades of Mandela’s life, as well as to explore the ANC’s turn to arms. The last but one section of the book, describing as it does Mandela’s pre-Robben Island trip through Africa, tells us not only of the man but of the continent and the era.

Yet I worried when the author’s sourcing was overtaken by its opposite: gossip, some of it salacious. As I read deeper through a patchwork of anecdote and allegation, it occurred to me that history is written not so much by its victors, but by its survivors. As the old guard fades and dies it is these survivors, some of whom feel shortchanged by the record, who seize the chance to insinuate their memories into the record. Many of their frequently carping opinions litter this book.

What is more worrying is that unattributed pronouncements may or may not be true. So, for example, why not tell us which “members of his own family” told the author that Mandela is not entirely selfless but also driven by an element of personal ambition? (A statement that is not exactly earth-shaking).

Or why not let us in on the secret of which “people close to Mandela” are confident enough to assert that a close friend, Ruth Mompati, had a child by him, something that Mompati denied? Or who were the “others” who suggested that Mandela’s daughter, Maki, might not have wanted to be interviewed for this book because she wanted to write her own? Or why should we even care that “someone outside the family” described Mandela’s son, Makgatho, as looking like him but without the charisma?

And, finally, by what authority, and as a result of what research, does the author suggest that Mandela might have been “embarrassed by this illiterate pipe smoking woman [his mother] with narrow horizons”? Such examples form the spine of what’s new here. This raises ethical issues. Sources do sometimes need protecting. But unnamed “others” and “people” have been used in the cause of a sensationalism for its own sake. What might have been a fascinating examination of the tensions between black and white in the broader movement, is debased by a prurient fascination with their sex lives.

As part of South Africa’s much vaunted truth and reconciliation process, perpetrators were granted amnesty in exchange for full disclosure. So in the interests of full disclosure, I must confess that stories of my parents, the antiapartheid activists Joe Slovo and Ruth First, some of which were quite new to me, also litter these pages. And in full disclosure’s further interests, I should also confess that I, too, have written a book about my parents not as heroes but as human – a worthwhile project, it seems to me. And yet undoubtedly it throws up ethical issues and, particularly when people are not around to comment, profound issues of veracity.

That Mandela is also human, with many of the frailties that attend us all, is no surprise. To explore his human side is an honourable enough project in itself. But the public chroniclers of other people’s lives also have a responsibility to decide what part of what they have been told is true and what is false. Should they not therefore weigh up the evidence rather than do what Smith has done, and throw in everything, the more incredible the better? Young Mandela provides its own fascination, not least because of the man himself and his world, which the author sometimes convincingly evokes. But its fascination with the very celebrity it pretends to scorn leaves a sour taste.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

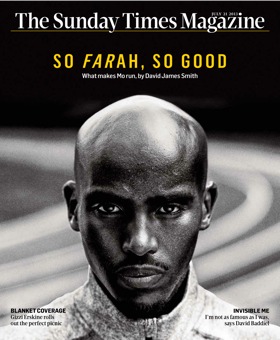

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011