The critics on Young Mandela

The Spectator – Andro Linklater

In June 1964, when Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment for acts of sabotage against the apartheid government of South Africa, he was, as photographs reveal, a burly, blackhaired man, with a handsome, pugnacious grin. By the time he was released in 1990, his hair was grey and his features gaunt. But his first speech as a free man described the same ideal of a democratic, multiracial South Africa that he had presented in his final address before being sentenced – ‘an ideal I hope to live for, but if needs be, an ideal for which I am prepared to die’. That imprisonment should neither have broken nor embittered him, and that he should then have realised his goal by guiding South Africa’s transition from apartheid to ‘rainbow nation’, stamped Mandela as an authentic hero.

Nevertheless, such a reputation demands to be tested, if only because standards of political and personal behaviour change over time. Mandela’s espousal of terrorism in 1961, for instance, is more difficult to justify today than it once was. David James Smith’s stated aim, ‘to write about him as a human being [with] flaws and weaknesses just like everyone else’, is no doubt intended to be part of the testing process.

He is certainly single-minded. In Smith’s judgment, Mandela is an ungrateful son, ’embarrassed’ by his illiterate, pipe-smoking mother, an unfaithful and violent husband, who attempted to throttle his first wife, Evelyn, and an unfeeling father who recoiled from his Aids-infected son. For good measure, he is also a crypto-communist, whose critical decision to steer the nonviolent African National Congress (ANC) towards a bombing campaign in 1961 was influenced by Marxist ideology.

On the face of it, this is a damning bill of indictment, apparently based on Smith’s research and on interviews he conducted with ANC survivors from the 1950s, and members of Mandela’s extended family. Closer examination, however, reveals a flakier construction, something more like the biocidalographies Kitty Kelley concocted about Nancy Reagan or the royal family. Accusations about Mandela’s private life, for example, his womanising, his relationship with his children, and his treatment of his first wife, are based primarily on rancorous gossip exchanged by members of Mandela’s two warring families, the descendants of Evelyn, and his second wife, Winnie. Except for Ndelika Mandela, however, an estranged grand-daughter and child of the son who died of Aids, firsthand sources rarely have any attribution beyond ‘there are rumours’, ‘there are suspicions’, ‘it is known’. The supposed ’embarrassment’ about his mother does not even have that foundation, simply being Smith’s response to a passage in Mandela’s autobiography that shows, if anything, affection.

Typical of the author’s approach is his attempt to discover evidence of Mandela’s womanising. With prurient curiosity, he asks almost every woman who might have had the opportunity whether she has slept with Mandela, yet fails to extract a single compromising admission. This does not prevent him from presenting their denials in a queasily knowing manner: ‘Even though you could imagine the potential for sexual tension’ he says of a former secretary who took Mandela’s dictation, ‘Amy insisted nothing ever happened.’ In the case of Ruth Monpati, a wholly respectable 83-year-old lady who specifically denied having a child by Mandela, Smith goes further and directly implies she is lying with the quote ‘people close to Mandela are confident in asserting that Ruth Monpati had a child by Mandela’.

Frustrated by their answers, he resorts to the bizarre assertion that whilst [Mandela] might have left behind the rural African society of his origins, he carried with him the values of that world, where men were free to have as many wives as they could afford.

Drowned in this rancid stew are issues that really need examination, about the personal and political costs of Mandela’s achievement. Thus, he may indeed have been physically violent towards his first wife. Although the only evidence is Evelyn’s assertion, soon withdrawn, in her petition for divorce, she did become a fervent Jehovah’s Witness in the early 1950s and thereafter firmly opposed any rebellion against government. Since Mandela was struggling towards outright, illegal opposition at the time, the tensions in the family might easily have reached breaking point.

That is one cost.

Politically, it seems equally plausible that his adoption of armed resistance to apartheid following the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 was influenced by friendship with communists like Joe Slovo. But while that legacy still motivates the violent egalitarianism of the ANC’s youth wing, the ANC’s middle-class supporters look back to Mandela’s decision in 1954 to defend blackowned Sophiatown against government bulldozers, on ‘the principle that blacks should have freehold rights’. Those internal contradictions, which still torment the ANC and threaten its future, are also part of the price.

Nothing in Young Mandela will affect the old lion’s reputation. What it will do to the author’s is another matter.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

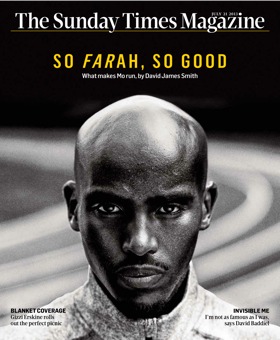

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011